This is a recording of a recent live teleclass I did with thousands of kids from all over the world. I’ve included it here so you can participate and learn, too!

Soar, zoom, fly, twirl, and gyrate with these amazing hands-on classes which investigate the world of flight. Students created flying contraptions from paper airplanes and hangliders to kites! Topics we will cover include: air pressure, flight dynamics, and Bernoulli’s principle.

Materials:

- 5 sheets of 8.5×11” paper

- 2 index cards

- 2 straws

- 2 small paper clips

- Scissors, tape

- Optional: ping pong ball and a small funnel

[am4show have=’p8;p9;p11;p38;p93;’ guest_error=’Guest error message’ user_error=’User error message’ ]

Key Concepts

While the kids are playing with the experiments see if you can get them to notice these important ideas. When they can explain these concepts back to you (in their own words or with demonstrations), you’ll know that they’ve mastered the lesson.

- Air pressure is all around us. Air pushes downward and creates pressure on all things.

- Air pressure changes all the time.

- Higher pressure always pushes.

- The faster air travels over a surface, the less time it has to push down on that surface and create pressure. Fast moving air creates low pressure regions. (Bernoulli’s Law).

- The four fundamental forces on an airplane are lift, weight, thrust, and drag.

What’s Going On?

There’s air surrounding us everywhere, all at the same pressure of 14.7 pounds per square inch (psi). You feel the same force on your skin whether you’re on the ceiling or the floor, under the bed or in the shower.

An interesting thing happens when you change a pocket of air pressure – things start to move. This difference in pressure causes movement that creates winds, tornadoes, airplanes to fly, and some of the experiments we’re about to do together.

An important thing to remember is that higher pressure always pushes stuff around. While lower pressure does not “pull,” we think of higher pressure as a “push”. The higher pressure inside a balloon pushes outward and keeps the balloon in a round shape.

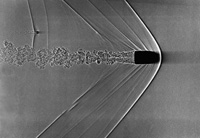

Weird stuff happens with fast-moving air particles. When air moves quickly, it doesn’t have time to push on a nearby surface, such as an airplane wing. The air just zooms by, barely having time to touch the surface, so not much air weight gets put on the surface. Less weight means less force on the area. You can think of “pressure” as force on a given area or surface. Therefore, a less or lower pressure region occurs wherever there is fast air movement.

There’s a reason airplane wings are rounded on top and flat on the bottom. The rounded top wing surface makes the air rush by faster than if it were flat. When you put your thumb over the end of a gardening hose, the water comes out faster when you decrease the size of the opening. The same thing happens to the air above the wing: the wind rushing by the wing has less space now that the wing is curved, so it zips over the wing faster, and creates a lower pressure area than the air at the bottom of the wing.

The Wright brothers figured how to keep an airplane stable in flight by trying out a new idea, watching it carefully, and changing only one thing at a time to improve it. One of their biggest problems was finding a method for generating enough speed to get off the ground. They also took an airfoil (a fancy word for “airplane wing”), turned it sideways, and rotated it around quickly to produce the first real propeller that could generate an efficient amount of thrust to fly an aircraft. Before the Wright brothers perfected the airfoil, people had been using the same “screw” design created by Archimedes in 250 BC. This twist in the propeller was such a superior design that modern propellers are only 5% more efficient than those created a hundred years ago by the two brilliant Wright brothers.

Questions to Ask

When you’ve worked through most of the experiments ask your kids these questions and see how they do:

- Higher pressure does which? (a) pushes (b) pulls (c) decreases temperature (d) meows (e) causes winds, storms, and airplanes to fly

- The tips on the edge of a paper airplane wing provide more lift by: (a) flapping a lot

(b) destroying wingtip vortices that kill lift (c) getting stuck in a tree more easily (d) decreasing speed - In the ping pong ball and funnel experiment, the ball stayed in the funnel was because: (a) you couldn’t blow hard enough (b) you glued it into the funnel (c) the ball had a hole in it (d) the fast blowing caused a low-pressure region around the ball, causing the surrounding atmospheric pressure to be a higher pressure, thus pushing the ball into the funnel

- If your plane takes a nose dive, you should try (a) changing the elevators by pinching the edges (b) change the dihedral angle (c) change how you throw it (d) all of the above

- What are the four forces that act on every airplane in flight?

- Draw a quick sketch of your plane viewed from the front with a positive dihedral.

- If you were designing your own “Flying Paper Machine Kit”, what would be inside the box?

- What’s the one thing you need to remember about higher pressure?

- What keep an airplane from falling?

- Where is the low pressure area on an airplane wing?

Answers:

1 (a, e) 2 (b) 3 (d) 4 (d) 5 (lift, weight, thrust, drag) 8 (higher pressure pushes) 9 (lift) 10 (top surface)

[/am4show]

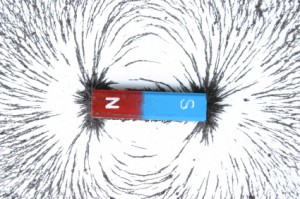

The electromagnetic field is a bit strange. It is caused by either a magnetic field or an electric field moving. If a magnetic field moves, it creates an electric field. If an electric field moves, it creates a magnetic field.

The electromagnetic field is a bit strange. It is caused by either a magnetic field or an electric field moving. If a magnetic field moves, it creates an electric field. If an electric field moves, it creates a magnetic field.

You are actually fairly familiar with electric fields too, but you may not know it. Have you ever rubbed your feet against the floor and then shocked your brother or sister? Have you ever zipped down a plastic slide and noticed that your hair is sticking straight up when you get to the bottom? Both phenomena are caused by electric fields and they are everywhere!

You are actually fairly familiar with electric fields too, but you may not know it. Have you ever rubbed your feet against the floor and then shocked your brother or sister? Have you ever zipped down a plastic slide and noticed that your hair is sticking straight up when you get to the bottom? Both phenomena are caused by electric fields and they are everywhere!

Did you know that your cereal may be magnetic? Depending on the brand of cereal you enjoy in the morning, you’ll be able to see the magnetic effects right in your bowl. You don’t have to eat this experiment when you’re done, but you may if you want to (this is one of the ONLY times I’m going to allow you do eat what you experiment with!) For a variation, pull out all the different boxes of cereal in your cupboard and see which has the greatest magnetic attraction.

Did you know that your cereal may be magnetic? Depending on the brand of cereal you enjoy in the morning, you’ll be able to see the magnetic effects right in your bowl. You don’t have to eat this experiment when you’re done, but you may if you want to (this is one of the ONLY times I’m going to allow you do eat what you experiment with!) For a variation, pull out all the different boxes of cereal in your cupboard and see which has the greatest magnetic attraction.

Things with gravity were going along just fine, until we started looking at the planets. It turns out that Mercury’s orbit doesn’t follow the math the way that it should – meaning that scientists can describe the orbits of the planets using complicated math equations… all except for Mercury.

Things with gravity were going along just fine, until we started looking at the planets. It turns out that Mercury’s orbit doesn’t follow the math the way that it should – meaning that scientists can describe the orbits of the planets using complicated math equations… all except for Mercury. Another thing that we know is that gravity is the weakest of the four fundamental forces on small scales (we’re talking about the size of atoms here). On large scales, however, it’s the force that keeps the planets in orbit, galaxies in orbit, and everything slinging around each other as they should. Think about when you stick a magnet to the fridge: the magnetic forces are keeping the magnet up (well, most of the time anyway!) and overcoming the gravitational field effects from the planet.

Another thing that we know is that gravity is the weakest of the four fundamental forces on small scales (we’re talking about the size of atoms here). On large scales, however, it’s the force that keeps the planets in orbit, galaxies in orbit, and everything slinging around each other as they should. Think about when you stick a magnet to the fridge: the magnetic forces are keeping the magnet up (well, most of the time anyway!) and overcoming the gravitational field effects from the planet.

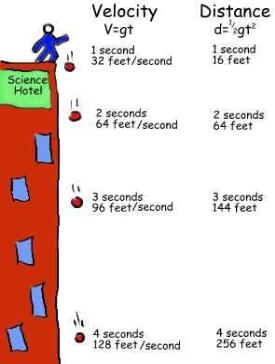

So you can see that as long as you accelerate, you will be getting faster and faster. The formula for this is v=at where v is velocity, a is acceleration and t is time. (We will be doing more with acceleration in a future lesson.)

So you can see that as long as you accelerate, you will be getting faster and faster. The formula for this is v=at where v is velocity, a is acceleration and t is time. (We will be doing more with acceleration in a future lesson.) Dry friction is just like it sounds – if you’ve ever tried to shove a heavy box across the pavement, you know that it’s harder to get it started than keep it going. That’s because when you first start to shove the box, you’ve got to overcome the (stronger) static friction, but once you’re moving you are dealing with only with the (weaker) kinetic friction. Sometimes kinetic friction is called ‘sliding’ or ‘dynamic’ friction.

Dry friction is just like it sounds – if you’ve ever tried to shove a heavy box across the pavement, you know that it’s harder to get it started than keep it going. That’s because when you first start to shove the box, you’ve got to overcome the (stronger) static friction, but once you’re moving you are dealing with only with the (weaker) kinetic friction. Sometimes kinetic friction is called ‘sliding’ or ‘dynamic’ friction.

Find a smooth, cylindrical support column, such as those used to support open-air roofs for breezeways and outdoor hallways (check your local public school or local church). Wind a length of rope one time around the column, and pull on one end while three friends pull on the other in a tug-of-war fashion.

Find a smooth, cylindrical support column, such as those used to support open-air roofs for breezeways and outdoor hallways (check your local public school or local church). Wind a length of rope one time around the column, and pull on one end while three friends pull on the other in a tug-of-war fashion.

Hovercraft transport people and their stuff across ice, grass, swamp, water, and land. Also known as the Air Cushioned Vehicle (ACV), these machines use air to greatly reduce the sliding friction between the bottom of the vehicle (the skirt) and the ground. This is a great example of how lubrication works – most people think of oil as the only way to reduce sliding friction, but gases work well if done right.

Hovercraft transport people and their stuff across ice, grass, swamp, water, and land. Also known as the Air Cushioned Vehicle (ACV), these machines use air to greatly reduce the sliding friction between the bottom of the vehicle (the skirt) and the ground. This is a great example of how lubrication works – most people think of oil as the only way to reduce sliding friction, but gases work well if done right.