This experiment is for advanced students.It’s time for the last lesson of mechanics. After all this time, you now have a good working knowledge of the rules that govern almost all movement on this planet and beyond!! This lesson we get to learn about things crashing into one another!! Isn’t physics fun?! We are going to learn about impulse and momentum.

This experiment is for advanced students.It’s time for the last lesson of mechanics. After all this time, you now have a good working knowledge of the rules that govern almost all movement on this planet and beyond!! This lesson we get to learn about things crashing into one another!! Isn’t physics fun?! We are going to learn about impulse and momentum.

[am4show have=’p9;p39;p92;’ guest_error=’Guest error message’ user_error=’User error message’ ]

Here’s what you need:

- two pennies

- you

- a wall

- wagon and a skateboard

- friends

Momentum

Momentum can be defined as inertia in motion. Something must be moving to have momentum. Momentum is how hard it is to get something to stop or to change directions. A moving train has a whole lot of momentum. A moving ping pong ball does not. You can easily stop a ping pong ball, even at high speeds. It is difficult, however, to stop a train even at low speeds. Mathematically, momentum is mass times velocity, or Momentum=mv. The heavier something is and/or the faster it’s moving the more momentum it has. The more momentum something has, the more force it takes to get it to change velocity and the more force it can apply if it hits something.

Impulse

Now let’s discuss impulse. Impulse is a measure of force and time. Remember, force is a push or a pull, right? Well, impulse is how much force is applied for how much time. Mathematically it’s impulse equals force x time or impulse = Ft.

Think about baseball. When you hit a baseball, do you just smack it with the bat or do you follow through with the swing? You follow through right? Do you see how impulse relates to your baseball swing? If you follow through with your swing, the bat stays in contact with the ball for a longer period of time. This causes the ball to go farther. Follow through is important in golf, bowling, tennis and many sports for the same reason. The longer the force is imparted, the farther and faster your ball will go.

More About Impulse and Momentum

Ok, let’s add impulse and momentum together and see what we get. Impulse changes momentum. If an object puts an impulse on another object, the momentum of both objects will change. If you continue to push on your stalled car, you will change the momentum of the car right? If you are riding your bike while not paying any attention and crash into the back of a parked car, you will put an impulse on the car and you and the car’s momentum will change. (As a kid, I did this pretty often. That’s what you get when you ride and wonder at the same time. Believe me when I tell you that my momentum changed a lot more than the car’s did!!)

Ok, let’s add impulse and momentum together and see what we get. Impulse changes momentum. If an object puts an impulse on another object, the momentum of both objects will change. If you continue to push on your stalled car, you will change the momentum of the car right? If you are riding your bike while not paying any attention and crash into the back of a parked car, you will put an impulse on the car and you and the car’s momentum will change. (As a kid, I did this pretty often. That’s what you get when you ride and wonder at the same time. Believe me when I tell you that my momentum changed a lot more than the car’s did!!)

In fact, there is a mathematical formula about this impulse and momentum thing. Impulse = change in momentum or Ft = change in mv. Force x time = mass x velocity. Does that sound familiar to anyone? It’s awfully similar to Newton’s second law (F=ma) isn’t it? In fact it’s the same thing.

**Alert, alert serious math here, feel free to skip this.**

F t = m v

Now if we divide both sides by “t” we get F=mv/t. Another way to say v is d/t (distance over time).

So now we have F=m(d/t)/t.

Those two “t’s” together are the same as t2 and d/t2 is a (acceleration). So what we have now is F=ma!

This Ft = mv is very important, in fact, it can save your life. Seat belts, air bags, crumple zones and other car safety features are based on this formula. When you want to shrink the force of impact, you want to increase the time the impact takes. This is called the collision time. The longer the collision time the longer it takes your momentum to come to zero. Here’s the math.

If you are in a 1000 kg vehicle moving at 30 km/h your momentum is 1000 x 30 or 30,000. Now, lets say you hit a brick wall so your momentum goes from 30,000 to 0 in .5 seconds.

Ft=mv so F(.5) = 30,000 so F= 60,000N! (N is for Newton which is a unit of force. It takes about 1 Newton to lift an apple so this car hits with the force of 60,000 apples! Talk about apple sauce!)

That’s gonna leave a mark! Now lets say that instead of hitting a brick wall you hit a mound of hay and so the impact takes 3 seconds.

Now the formula looks like this: F(3)=30,000 or F= 10,000N.

See the difference, 60,000N versus 10,000N of force. All those safety features, seat belts, helmets, air bags, are designed to increase how long it takes your momentum to come to zero. Newton’s laws to the rescue! Let’s do a couple of experiments here to help this information have more impact (pun intended!).

Quick Momentum Experiment

1. Find a wall.

2. Hit it with your bare fist. Take it easy, just hit it with enough force that you feel the impact.

3. Now put a pillow in front of the wall and hit it with about the same force as you hit it before.

4. With the pillow in front of the wall, you can hit it a little harder if you like but again, don’t go nuts!

What did the pillow do? It slowed the time of impact. Remember our formula Ft=mv. When the momentum of your moving fist struck the wall directly, the momentum was cut to zero instantly and so you felt enough force to hurt a bit. When the pillow was in the way it took longer for your momentum to come to zero. So you could hit the pillow fairly hard without feeling much force. Basically a bike helmet is like a pillow for you head. It slows the time of impact, so when you fall off your bike, there is much less force on your head. Just be glad your mom doesn’t make you wear a pillow on your head!

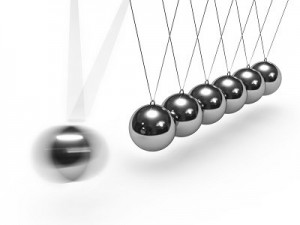

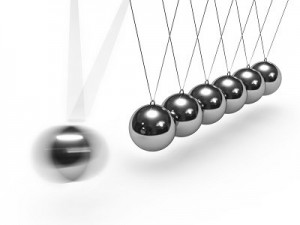

So let’s go back to momentum for a minute. Momentum is inertia in motion. It is how much force it takes to get something to slow down or change direction. One more concept I’d like to give you this month, is conservation of momentum. This is basically momentum equals momentum or mathematically mv=mv. (Momentum is mass times velocity.) When objects collide, the momentum that both objects have after the collision, is equal to the amount of momentum the objects had before the collision. Let’s take a look at this with this experiment.

Another Quick Momentum Experiment

1. Put one penny on the table.

2. Put another penny on the table about 6 inches away from the first one.

3. Now, slide one penny fairly fast towards the first penny.

4. What you want to have happen, is that the moving penny strikes (or gives impulse to) the stationary penny head on. The moving penny should stop and the stationary penny will move.

5. Now, try that with other coins. Make big ones hit small ones and vice versa. It’s also fun to put a line of 5 coins all touching one another. Then strike the end of the line with a moving penny.

This is conservation of momentum. If you were able to strike the penny head on, you should have seen that the penny that was moving, stopped, and the penny that was stationary moved with about the same speed of the original moving penny. Conservation of momentum is mv = mv. Once the moving penny struck the other, all the moving penny’s momentum transferred to the second penny. Since the pennies weighed the same, the v (velocity) of the first penny is transferred to the second penny and the second penny moves with the same velocity as the first penny. What happens if you use a quarter and a penny? Make the quarter strike the penny. That penny should really zip! Again mv=mv. The mass of the quarter is much greater then the mass of the penny. So for momentum to be conserved, after impact, the penny had to have a much greater velocity to compensate for its lower mass.

Mathematically it would look like this (the masses are not accurate to make the math easier to see.)

After collision Mass of Quarter x Velocity of Quarter = Mass of Penny x Velocity of Penny

5g x 10m/s = 1g x v

50 = 1 x v

50/1 = v

50m/s = v

or 5g x 10m/s = 1g x 50 m/s

50 momentum = 50 momentum

After the collision, the penny is moving at 50 m/s, 5 times faster then the quarter was moving because the penny is 5 times lighter then the quarter.

And ANOTHER Quick Momentum Experiment

Do this experiment again, but this time make the cork heavier. I wrapped mine in duct tape and then jammed a roll of electrical tape on the end. If you wanted to tape a golf ball to the cork or tape a bunch of change to it it would work as well. Just try to make the cork a good bit heavier than it was in the first place.

Do this experiment again, but this time make the cork heavier. I wrapped mine in duct tape and then jammed a roll of electrical tape on the end. If you wanted to tape a golf ball to the cork or tape a bunch of change to it it would work as well. Just try to make the cork a good bit heavier than it was in the first place.

This is a great example of impulse as well as conservation of momentum. The impulse (Ft) is the baking soda and vinegar gas mixture creating enough pressure to force the cork off the bottle. According to Newton’s Third Law, the force from that impulse has an equal and opposite reaction, so the bus goes one way and the cork goes the other. Now take that information and combine it with what you now know about conservation of momentum. The impulse is equal for the cork and the bus, so which one is going to have more velocity due to it’s lighter mass? The cork. mv=mv. Just like the penny and the quarter, the lighter cork will go farther than the heavier bus. Now if you make the cork heavier and try it again, what will you see? Now the bus moves farther but the cork moves less far. Again, conservation of momentum, mv = mv.

Yet ANOTHER Easy Momentum Activity

1. Put the wagon and the skateboard close to one another.

2. Have one person sit on the skateboard while the other sits on the wagon.

3. Make sure the wheels are straight on the wagon and that the sidewalk is relatively free of stuff in the way.

4. Have one person give a good shove to the other person. Usually, it is easier for the person on the skateboard to push on the wagon. If this is true with your setup, then do it that way. Otherwise, do whatever is easiest.

5. Feel free to add more people or weight to the wagon and try it again.

Can you see how this and the one before it are really showing the same concept? Who went farther and faster? The lighter person on the lighter vehicle right? The impulse of the push was the same for both vehicles, so both vehicles had the same momentum. Momentum is mass and velocity so if the mass for both vehicles was the same, the speed would be the same. If the mass of one was more then the mass of the other, then the heavier one would move more slowly then the lighter one.

Highlights for Momentum & Impulse

Impulse is the amount of time a force is put on an object. How hard and how long something gets pushed or pulled.

Ft = Impulse. Impulse affects the momentum of an object.

Momentum is inertia in motion, how hard it is to get something to change directions or speed. Momentum = mv.

Conservation of momentum; mv = mv. If something hits something else the momentum of the objects before the collision will equal the momentum of the objects after the collision.

Here is another experiment in momentum: Newton’s Second Law.

Advanced students: Download your Momentum lab here.

Download Student Worksheet & Exercises

Exercises

- What is momentum?

- What is impulse?

- What is the conservation of momentum?

[/am4show]

The atoms in a solid, as we mentioned before, are usually held close to one another and tightly together. Imagine a bunch of folks all stuck to one another with glue. Each person can wiggle and jiggle but they can’t really move anywhere.

The atoms in a solid, as we mentioned before, are usually held close to one another and tightly together. Imagine a bunch of folks all stuck to one another with glue. Each person can wiggle and jiggle but they can’t really move anywhere.

Can we really make crystals out of soap? You bet! These crystals grow really fast, provided your solution is properly saturated. In only 12 hours, you should have sizable crystals sprouting up.

Can we really make crystals out of soap? You bet! These crystals grow really fast, provided your solution is properly saturated. In only 12 hours, you should have sizable crystals sprouting up.

You should see a bluish or yellowish light coming from the middle section of the grape. This is plasma! Be careful not to overcook the grape. It will smoke and stink if you let it overcook. Also, make sure the grape has time to cool before taking it out of the microwave.

You should see a bluish or yellowish light coming from the middle section of the grape. This is plasma! Be careful not to overcook the grape. It will smoke and stink if you let it overcook. Also, make sure the grape has time to cool before taking it out of the microwave.

A gram of water (about a thimble of water) contains 1023 atoms. (That’s a ‘1’ with 23 zeros after it.) That means there are 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 atoms in a thimble of water! That’s more atoms than there are drops of water in all the lakes and rivers in the world.

A gram of water (about a thimble of water) contains 1023 atoms. (That’s a ‘1’ with 23 zeros after it.) That means there are 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 atoms in a thimble of water! That’s more atoms than there are drops of water in all the lakes and rivers in the world.

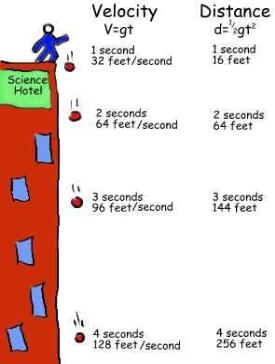

This experiment is one of my favorites in this acceleration series, because it clearly shows you what acceleration looks like.

This experiment is one of my favorites in this acceleration series, because it clearly shows you what acceleration looks like.

Gyroscopes defy human intuition, common sense, and even appear to defy gravity. You’ll find them in aircraft navigation instruments, games of Ultimate Frisbee, fast bicycles, street motorcycles, toy yo-yos, and the Hubble Space Telescope. And of course, the toy gyroscope (as shown here). Gyroscopes are used at the university level to demonstrate the principles of angular momentum, which is what we’re going to learn about here.

Gyroscopes defy human intuition, common sense, and even appear to defy gravity. You’ll find them in aircraft navigation instruments, games of Ultimate Frisbee, fast bicycles, street motorcycles, toy yo-yos, and the Hubble Space Telescope. And of course, the toy gyroscope (as shown here). Gyroscopes are used at the university level to demonstrate the principles of angular momentum, which is what we’re going to learn about here.

Let's take a good look at Newton's Laws in motion while making something that flies off in both directions. This experiment will pop a cork out of a bottle and make the cork fly go 20 to 30 feet, while the vehicle moves in the other direction!

Let's take a good look at Newton's Laws in motion while making something that flies off in both directions. This experiment will pop a cork out of a bottle and make the cork fly go 20 to 30 feet, while the vehicle moves in the other direction!

Every wonder why you have to wear a seat belt or wear a helmet? Let's find out (safely) by experimenting with a ball.

Every wonder why you have to wear a seat belt or wear a helmet? Let's find out (safely) by experimenting with a ball.

This is a quick and easy demonstration of how to teach Newton’s laws with minimal fuss and materials. All you need is a wagon, a rock, and some friends. We’re going to do a few totally different experiments using the same materials, though, so keep up with the changes as you read through the experiment.

This is a quick and easy demonstration of how to teach Newton’s laws with minimal fuss and materials. All you need is a wagon, a rock, and some friends. We’re going to do a few totally different experiments using the same materials, though, so keep up with the changes as you read through the experiment.

This experiment is for advanced students.It’s time for the last lesson of mechanics. After all this time, you now have a good working knowledge of the rules that govern almost all movement on this planet and beyond!! This lesson we get to learn about things crashing into one another!! Isn’t physics fun?! We are going to learn about impulse and momentum.

This experiment is for advanced students.It’s time for the last lesson of mechanics. After all this time, you now have a good working knowledge of the rules that govern almost all movement on this planet and beyond!! This lesson we get to learn about things crashing into one another!! Isn’t physics fun?! We are going to learn about impulse and momentum. Ok, let’s add impulse and momentum together and see what we get. Impulse changes momentum. If an object puts an impulse on another object, the momentum of both objects will change. If you continue to push on your stalled car, you will change the momentum of the car right? If you are riding your bike while not paying any attention and crash into the back of a parked car, you will put an impulse on the car and you and the car’s momentum will change. (As a kid, I did this pretty often. That’s what you get when you ride and wonder at the same time. Believe me when I tell you that my momentum changed a lot more than the car’s did!!)

Ok, let’s add impulse and momentum together and see what we get. Impulse changes momentum. If an object puts an impulse on another object, the momentum of both objects will change. If you continue to push on your stalled car, you will change the momentum of the car right? If you are riding your bike while not paying any attention and crash into the back of a parked car, you will put an impulse on the car and you and the car’s momentum will change. (As a kid, I did this pretty often. That’s what you get when you ride and wonder at the same time. Believe me when I tell you that my momentum changed a lot more than the car’s did!!) Do

Do

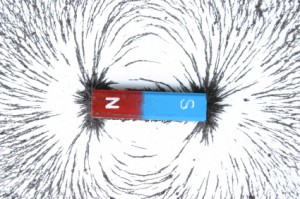

The electromagnetic field is a bit strange. It is caused by either a magnetic field or an electric field moving. If a magnetic field moves, it creates an electric field. If an electric field moves, it creates a magnetic field.

The electromagnetic field is a bit strange. It is caused by either a magnetic field or an electric field moving. If a magnetic field moves, it creates an electric field. If an electric field moves, it creates a magnetic field.

You are actually fairly familiar with electric fields too, but you may not know it. Have you ever rubbed your feet against the floor and then shocked your brother or sister? Have you ever zipped down a plastic slide and noticed that your hair is sticking straight up when you get to the bottom? Both phenomena are caused by electric fields and they are everywhere!

You are actually fairly familiar with electric fields too, but you may not know it. Have you ever rubbed your feet against the floor and then shocked your brother or sister? Have you ever zipped down a plastic slide and noticed that your hair is sticking straight up when you get to the bottom? Both phenomena are caused by electric fields and they are everywhere!

Did you know that your cereal may be magnetic? Depending on the brand of cereal you enjoy in the morning, you’ll be able to see the magnetic effects right in your bowl. You don’t have to eat this experiment when you’re done, but you may if you want to (this is one of the ONLY times I’m going to allow you do eat what you experiment with!) For a variation, pull out all the different boxes of cereal in your cupboard and see which has the greatest magnetic attraction.

Did you know that your cereal may be magnetic? Depending on the brand of cereal you enjoy in the morning, you’ll be able to see the magnetic effects right in your bowl. You don’t have to eat this experiment when you’re done, but you may if you want to (this is one of the ONLY times I’m going to allow you do eat what you experiment with!) For a variation, pull out all the different boxes of cereal in your cupboard and see which has the greatest magnetic attraction.

So you can see that as long as you accelerate, you will be getting faster and faster. The formula for this is v=at where v is velocity, a is acceleration and t is time. (We will be doing more with acceleration in a future lesson.)

So you can see that as long as you accelerate, you will be getting faster and faster. The formula for this is v=at where v is velocity, a is acceleration and t is time. (We will be doing more with acceleration in a future lesson.)

Find a smooth, cylindrical support column, such as those used to support open-air roofs for breezeways and outdoor hallways (check your local public school or local church). Wind a length of rope one time around the column, and pull on one end while three friends pull on the other in a tug-of-war fashion.

Find a smooth, cylindrical support column, such as those used to support open-air roofs for breezeways and outdoor hallways (check your local public school or local church). Wind a length of rope one time around the column, and pull on one end while three friends pull on the other in a tug-of-war fashion.

Hovercraft transport people and their stuff across ice, grass, swamp, water, and land. Also known as the Air Cushioned Vehicle (ACV), these machines use air to greatly reduce the sliding friction between the bottom of the vehicle (the skirt) and the ground. This is a great example of how lubrication works – most people think of oil as the only way to reduce sliding friction, but gases work well if done right.

Hovercraft transport people and their stuff across ice, grass, swamp, water, and land. Also known as the Air Cushioned Vehicle (ACV), these machines use air to greatly reduce the sliding friction between the bottom of the vehicle (the skirt) and the ground. This is a great example of how lubrication works – most people think of oil as the only way to reduce sliding friction, but gases work well if done right.

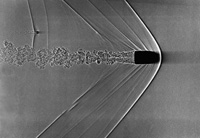

Sound is everywhere. It can travel through solids, liquids, and gases, but it does so at different speeds. It can rustle through trees at 770 MPH (miles per hour), echo through the ocean at 3,270 MPH, and resonate through solid rock at 8,600 MPH.

Sound is everywhere. It can travel through solids, liquids, and gases, but it does so at different speeds. It can rustle through trees at 770 MPH (miles per hour), echo through the ocean at 3,270 MPH, and resonate through solid rock at 8,600 MPH.

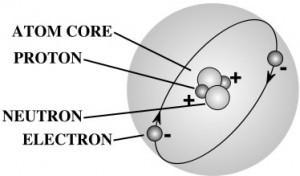

The smallest thing around is the atom, which has three main parts – the core (nucleus) houses the protons and neutrons, and the electron zips around in a cloud around the nucleus.

The smallest thing around is the atom, which has three main parts – the core (nucleus) houses the protons and neutrons, and the electron zips around in a cloud around the nucleus.