This is a recording of a recent live teleclass I did with thousands of kids from all over the world. I’ve included it here so you can participate and learn, too!

We’re going to study electrons and static charge. Kids will build simple electrostatic motor to help them understand how like charges repel and opposites attract. After you’ve completed this teleclass, be sure to hop on over the teleclass in Robotics!

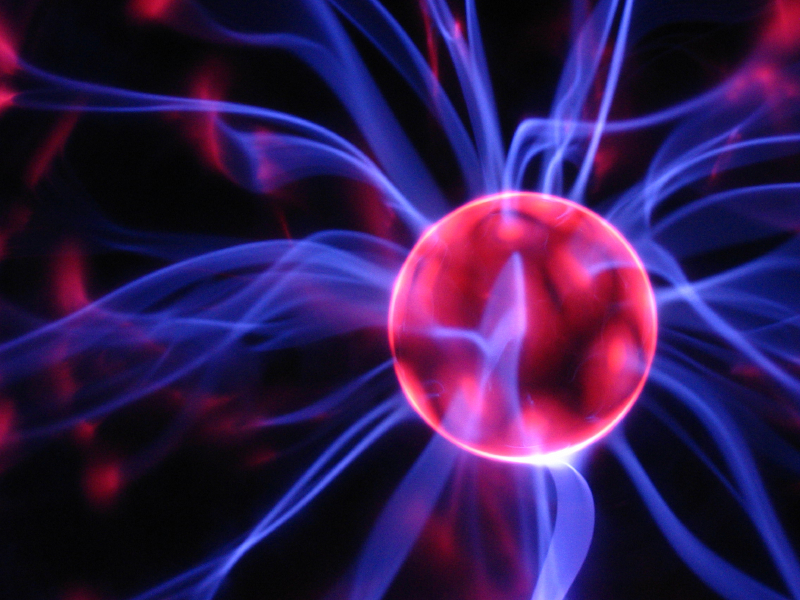

Electrons are strange and unusual little fellows. Strange things happen when too many or too few of the little fellows get together. Some things may be attracted to other things or some things may push other things away. Occasionally you may see a spark of light and sound. The light and sound may be quite small or may be as large as a bolt of lightning. When electrons gather, strange things happen. Those strange things are static electricity.

Please login or register to read the rest of this content.

Make yourself a grab bag of fun things to test: copper pieces (nails or pipe pieces), zinc washers, pipe cleaners, Mylar, aluminum foil, pennies, nickels, keys, film canisters, paper clips, load stones (magnetic rock), other rocks, and just about anything else in the back of your desk drawer.

Make yourself a grab bag of fun things to test: copper pieces (nails or pipe pieces), zinc washers, pipe cleaners, Mylar, aluminum foil, pennies, nickels, keys, film canisters, paper clips, load stones (magnetic rock), other rocks, and just about anything else in the back of your desk drawer.

When you turn on a switch, it’s difficult to really see what’s going on… which is why we make our own from paperclips, brass fasteners, and index cards.

When you turn on a switch, it’s difficult to really see what’s going on… which is why we make our own from paperclips, brass fasteners, and index cards.

So now you know how to hook up a

So now you know how to hook up a

Electrical circuits are used for all kinds of applications, from blenders to hair dryers to cars. And games! Here’s a quick and easy game using the principles of conductivity.

Electrical circuits are used for all kinds of applications, from blenders to hair dryers to cars. And games! Here’s a quick and easy game using the principles of conductivity.

One of the most useful tools a scientist can have! A

One of the most useful tools a scientist can have! A

The smallest thing around is the atom, which has three main parts – the core (nucleus) houses the protons and neutrons, and the electron zips around in a cloud around the nucleus.

The smallest thing around is the atom, which has three main parts – the core (nucleus) houses the protons and neutrons, and the electron zips around in a cloud around the nucleus.

This simple FET circuit is really an electronic version of the

This simple FET circuit is really an electronic version of the

It’s easy to use chemistry to generate electricity, once you understand the basics. With this experiment, you’ll use aluminum foil, salt, air, and a chemical from an aquarium to create an air battery. This experiment is for advanced students.

It’s easy to use chemistry to generate electricity, once you understand the basics. With this experiment, you’ll use aluminum foil, salt, air, and a chemical from an aquarium to create an air battery. This experiment is for advanced students.